Specimens Are Us

By Ralph Maltese

The names in this story have been changed to protect the innocent….and the guilty.

I was diagnosed with high cholesterol since forever. My family had a history of heart disease. When we settled in Pennsylvania, we found our family physician who cared for us for over forty years. Every six months I would find myself, before my teaching day began, in Dr.Galen’s office, arm outstretched, rubber tube wrapped around my upper arm, waiting for the pinch. “this will be a small sting.” he would forewarn, Sometimes, depending on the results of the previous metabolic panel, I would give a sample every three months. When the four vials were filled, Dr. Galen would hand me a small plastic jar and ask me to go to the bathroom across the hall from his office and provide a urine specimen. A few minutes later I would return to his office, I and my specimen, write a check to the good doctor, and I was on my way to teach my first period class, “mythological structures in The Grapes of Wrath.”

A decade or so later Dr. Galen decided it was more efficient if I gave a blood sample and a specimen at a lab closer to Alexander High School.Nearby Alexander Memorial Hospital housed most of my specialists, cardiologists, dermatologists, etc. As another decade passed, the locations of the ritual of drawing my blood and collecting a specimen changed until finally a lab opened up a mile from my home. The blood tests required I fast for 12 hours so I would get to Alexander’s lab around 7AM, scarf down a bagel or a banana on the way to Alexander High, after filling some vials and a jar.

The process in the lab would strolling past the three booths where three nice ladies were in the process of taking information from people about to part with bodily fluids, and up to a volunteer who would write my name on a clipboard thus cementing my place in the first come/first served list. Then I would sit down until the nice volunteer would call my name.

There was little conversation amongst the blood givers. I would read until the volunteer shouted my name and told me which booth to go to. “RALPH, BOOTH 3!!” At Booth 3 Ms. Penelope would smile and ask for the script from Dr. Galen ordering the tests, my medical cards, driver’s license, etc. all of which she typed into the computer on her desk…you know, the important stuff the insurance companies needed. Sometimes there would be difficulties because a doctor who ordered the tests would enter the wrong code which would bring the entire health care community to a halt. But eventually all miscommunications would be resolved and Alexander Memorial Hospital was confident it would get paid. Ms. Penelope would hand me a form to give to the phlebotomist, and I would return to the quiet waiting room, open my book and wait. Jerry Seinfeld noticed that everyone knows what to expect in a room called a Waiting Room. But this lab was pretty fast, and only a few minutes later I would hear my name and follow a phlebotomist pulling on blue latex gloves which matched her dark blue uniform as she led me to the small room with a big dentist-like chair, and hundreds of vials on the shelves.

“How are you today? Which arm do you want me to use?”

“Fine, thank you. Right arm.”

Her name tag says “Donna.” I would sit down in the ocean green lab chair, roll up my sleeve and watched as she prepared the vials and the other tools of the phlebotomist trade.

Donna made sure she was sticking the right person by asking me to identify myself by name and date of birth. The latex tube wrapped around my arm, Donna telling me to make a fist, Donna looking for a vein to use, tapping on the vein, and warning me “You’ll feel a pinch.” A few minutes later four vials of my blood are resting next to Donna’s computer. She puts two inches of gauze on the insertion point, straps the gauze with a Band-Aid, tells me to raise my arm and put pressure on the gauze for about five minutes, and then Donna hands me a small jar.

“Go the bathroom near the entrance, provide a specimen, and put it in the blue box in the next room. Have a good day!” Big smile.

It was not always easy to provide a specimen with one hand pressing down on the gauze but when it was accomplished, it was easy to just take the small jar into the next room and place it in the blue box with all the other jars. I was grateful for the Alexander Memorial Hospital Lab’s protocol which allowed for a rather discreet provision of a specimen. I would very discreetly skip from the bathroom to drop my jar in the blue box in the room next door, avoiding everyone’s eyes.

This procedure lasted for at least fifteen years. I was happy with it. At the very least it was a routine I was familiar with.

Enter Fillmore Enterprises. Not being a businessman, I do not know whether Fillmore Enterprises merged with Alexander Memorial Hospital. Fillmore replaced Alexander Memorial Hospital’s lab services with Specimens Are Us.. All I know is that my health care community had changed. Several of my doctors/specialists retired, including Dr. Galen. Their recommendations for their replacements turned out to be exceptional, and I was very happy with their choices. I was especially fortunate to have Dr. Galen’s replacement, Dr. Shire. She wanted the usual metabolic panel workup, so early one morning I went to the lab and saw a line of people in front of the three booths. I looked past the crowd to find the volunteer so I could sign in. No volunteer. People with crutches, people in wheelchairs, the very elderly struggling to stand on wobbly knees; all forming two lines that led to two white and blue kiosks. I got in line and waited. And waited. And waited. A fragile lady in her nineties wearing a checkered black and white houndstooth cap finally found herself in front of the kiosk. She looked around. “What do I do?” Someone pointed to a placard on the wall, but the houndstooth cap lady did not see the placard, until a younger woman sporting a yellow scarf touched her elbow and gently turned her to the placard.

“Instructions for Entering Information

TAP THE SCREEN AND FOLLOW THE INSTRUCTIONS”

The ninety-something lady tapped the screen. “Now what do I do?”

After approximately ten or fifteen minutes, with the help of the yellow scarfed woman, the houndstooth cap lady finished and slowly made her way to the waiting room chairs.

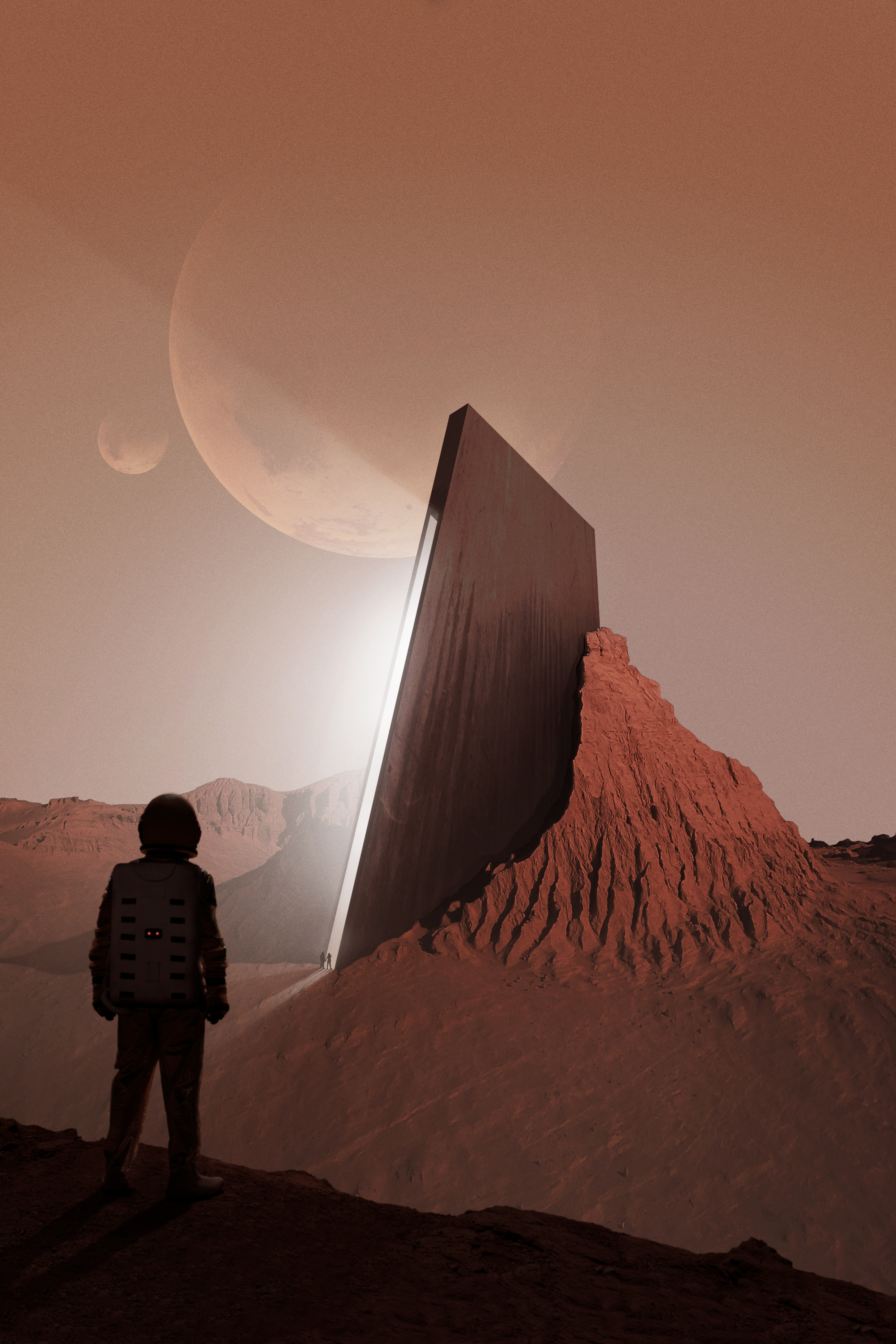

Several light years later, I found myself before the blue and white kiosk, the image of the monolith in the movie, 2001: A Space Odyssey, flashed in my brain.

I tapped the screen. Suddenly this title zoomed out in huge red letters!! WELCOME TO SPECIMENS ARE US

I see two options on the screen: MYSELF OTHER PERSON

I click on MYSELF and this comes up on the screen:

/mīˈself/

pronoun

- used by a speaker to refer to himself or herself as the object of a verb or preposition when he or she is the subject of the clause:”I hurt myself by accident”

I did not need the definition of myself. Did Fillmore/Alexander become a holistic medicine sort of institution? I pressed “MYSELF” again and the screen splashed a typical form asking information about me: name, date of birth, medical history, medications I am taking, allergies, family history, what did my maternal great grandmother die of, you know, the usual which, of course, has been in Fillmore/Alexander’s databank since 1970. I also had to insert my Medicare card, my supplemental insurance card, and driver’s license, but there were no directions on how to slide each card into the demanding monster. I can hear the moans and groans of the poor people behind me, and I worked as fast as I could.

When I finished, I was told to go to cubicle #3. I sat across from Ms. Greenfield who asked for my hospital cards, driver’s license, and script (request by doctor for the blood samples and urine specimen).

“I believe my doctor faxed over the script.” Ms. Greenfield rose from her chair and retrieved from a group of baskets the script and returned to type in some of the same information I had just typed into the WELCOME TO SPECIMENS ARE US monolith five minutes ago. Ms. Greenfield was very efficient and pleasant and said, “Please take a seat in the waiting room and we will call you when it is your turn. BUT, before you do, provide a specimen. She handed me a small jar and pointed to a bathroom across the line of people waiting to feed information into the WELCOME TO SPECIMENS ARE US monolith. I garbled out something like, “Ya mean now?” Ms. Greenfield nodded emphatically and, using her extended arm and index finger as an exclamation point gestured toward the bathroom.

I emerged from the bathroom holding my book in one hand and my specimen jar in the other and found a seat amongst the other patients in the waiting room. It was as quiet as a winter night in the forest with snow falling. I looked at the people around me and noticed what little talk existed was intermittently pierced by a tiny discussion about the weather. I felt awkward sitting with strangers trying not to look at each other’s specimen jar, and, except for two elderly gentlemen discussing local eateries, there was little talk about food.

I read my book, and, in a short time, I heard a gruff male voice bellow “Ralph!”

I rose and turned to see a phlebotomist with long dark black hair and a blue apron draping her body. Her lapel label said “Angie.” Book and specimen jar in hand, I strolled to the room Angie designated, sat down in the executioner’s chair, rolled up my shirt sleeve and awaited the draining. I handed my specimen jar to Angie who barely looked at it and placed it on a shelf.

“Okay, dearie, what’s your date of birth?” she said in a rather husky voice that implied she was a smoker. Dearie? When I would go Christmas shopping for Polley, I avoided women’s clothing stores if the saleslady addressed me as “Dearie.” To me, it is as if I said to Angie, “Hey, Babe, how’s it goin’?” I think it is a generational thing.

She then wrapped the latex tube around my upper arm and did the blood letting procedure.

A much younger phlebotomist entered the room, holding three vials of blood.

“Angie, what do I do with these?”

Angie looked up from her drawing my blood.

“You gotta tag them first.”

“I don’t know how to do that.”

“Take the strip with the patient’s personal data and wrap it around the vial.”

“Oh, okay.”

The younger phlebotomist left the room and Angie was on the third vial.

The younger phlebotomist returned seconds later.

“Angie, where do I get the patient’s personal data?”

Angie inhaled deeply and exhaled and coughed. “You download from the database on your computer. “

“Whattcha mean?”

“The computer on your desk. Open it up, type in your patient’s last name and his file should come up. The data is there. If you didn’t open his file, how did you know how much blood to take? It’s the same file with the PCL file you downloaded.”

“Oh! I was supposed to do that first?”

Angie shook her head slowly and inhaled again. Then she bolted upright. “Yes. Let me finish with this guy, and I’ll show you.”

“Okay.” The younger phlebotomist retreated to her room.

Angie looked at me, her eyes asking for pity, some empathy from me for her endurance of the younger generation. She took the needle out of my arm, applied the gauze and band-aid, and said, “You’re all done. Have a great day.” I was glad I had Angie as my phlebotomist.

“You, too. Thanks.”

I walked out of her room, my left index finger putting pressure on the gauze on my right arm. The line of people waiting to feed the Specimens Are Us monolith had grown. Fillmore, which I later learned had sold many of its MRI machines because it was in enormous debt, also closed its physical therapy gym to save money. That was sad because many of us who had heart problems (I had a bypass in 1989 and went to the gym 3 times a week} believed the medical community’s continual advice on the benefit of routine exercise for cardiac issues. I guess Fillmore no longer believed that. I guess they also believed that they could not afford a volunteer for the lab.

I stood for a moment at the door of the Specimens Are Us lab. I have no doubt that the modernization of medicine, the technological advancements in diagnosing and treating the human body have extended the longevity of people’s lives. But with every gain there is a loss, the fading of the family doctor for instance; you know, the doctor who knows you as a person and not as a collection of medical statistics. There is something about the social climate of a waiting room occupied by people, often nervous people, infirm or on crutches or in wheelchairs, which is somehow impacted by the presence of urine samples.

“Ma’am, I’m sure the lab will know whose is whose.” What can be more personal, and, surprisingly so impersonal at the same time?

“Ma’am, I’m sure the lab will know whose is whose.” What can be more personal, and, surprisingly so impersonal at the same time?

Having just had blood drawn, I fully empathize with your visit!

You have nailed it, Ralph, in a very entertaining way. It requires far more patience and endurance to navigate the seemingly improved medical system.